Why Singaporean Art?

As a citizen of Korea, a country which has only one ethnicity and one language, I am used to identifying myself by my language and my people. Then, this monocultural person arrives at a multicultural nation, Singapore.

Indeed, Singapore is one of the most culturally diverse nations in the world, with a number of ethnicities, languages, and religions. I had to wonder: what does it mean to be multicultural, and what does multiculturalism look like in Singapore?

Although it is a familiar term, culture is a difficult concept to understand. The way I would understand culture is that it is formed when people concretize their common actions in various parts of their lives. As time goes by, culture may change as one era or generation changes to the next. Regardless, culture lives in the present, representing only that moment; it may change, but always with improvements, as people learn from the past to create the best possible present. Art also is a representation of the era and therefore, helps to define culture itself - it embodies the spirit and lives of the people at a given moment. To understand how a culture has established and improved itself in terms of culture and tradition, one must look at its art.

To begin to understand Singaporean art, and thus the identity of the Singaporean, it is important to look at its origin, the Malay heritage. Singapore originally is a part of the Malay Archipelago, whose language originally was Malay and whose religion, for many centuries, has been Islamic, simply put. The Malay language, in particular, has been the defining aspect of the Malay culture. Once regarded as a lingua franca, the Malay language was used to imbue cultural identity to the region. One example of artwork that emphasizes this analytical language is Byword by Shahrul Jamili, a Malay artist.

He engraved onto a metal piece of origami a warning from the Malay linguist Za’ba that Jawi script, the Arabic alphabet, used primarily to write the Malay language has become an obsolete “byword,” thus being “decorative and romantic.” This work can be interpreted as Jamili’s own message about the importance of keeping the roots of the Malay language, so that the language may be savored. Singapore is not an exception when it comes to appreciating the value of languages in building cultural identities.

The use of language in art is a controversial topic among artists and critics - some argue that art should speak to people regardless of their linguistic abilities. However, the language seems to be an inseparable motif of Singaporean art as a way of defining the individuals’ origin. The influx of languages has become an important change that characterizes modern Singapore. Currently, English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil (spoken in India) are official languages of Singapore. In such a multilingual country, a language can be both a spirit to identify a cultural community and a tool to communicate.

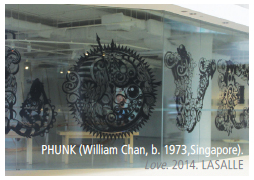

This idea is reflected in art: Shadow Forest generates the shadows of Malay words perforated on metal plates, forming a forest. The glass buildings on the campus of LASALLE College of the Arts are covered with inspirational words such as expression, collaboration, sensibility, and culture. One LASALLE student contributed the most powerful word - Love. Language for them is a barrier to overcome, yet a home of their own.

The Peranakans are an inseparable part of Singapore. Peranakans are descendants of offspring between traders from all over the world and local Southeast Asian wives. Among the many Peranakan communities, the Baba community from the Chinese is the most predominant of all, and its Chinese culture and tradition have greatly influenced traditional rituals and life styles of the Peranakan of Singapore. To understand Peranakan, again, one must look at its art.

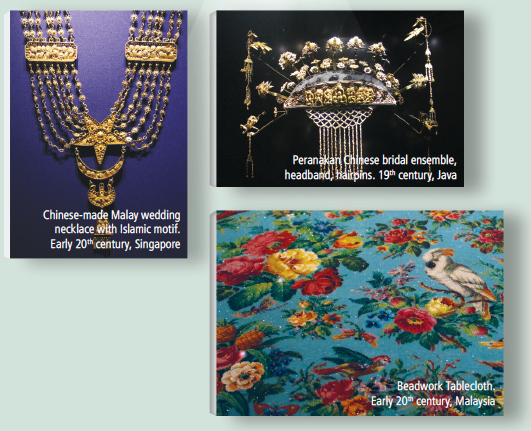

One of the Peranakan artifacts that shows a characteristic of Peranakan culture is the hybrid jewelry used in matrimonial ceremonies. This characteristic is the principle of coexistence, cooperative living of various cultures together. When two different societies come into contact, it is common for the culture and religion that have been present longer to be diluted and eventually replaced by the newer arrivals. Such is not the case for the Peranakans in Singapore.

By examining wedding ornaments, we can learn much about a culture’s standards or traditions of craftsmanship, as well as deeper cultural aspects, in the same way that we learn from artifacts found in tombs. One thing we can observe is that a significant amount of time, effort, and money go into the making of these ornaments, so that they will epitomize the very soul of a culture.

We can observe cultural synthesis taking place. When the Chinese who form the base of the Peranakans first arrived, the local culture was Malay or Javanese. The floral hairpins and headbands resemble bridal ornaments from Malay communities such as Java, but symbols on the headpiece include Chinese pictographs. It seems that local Malay craftsmen used  , the auspicious Chinese Eight Immortals, to decorate the ornament unaware of its original symbolism. Another example of this cross-cultural interaction is a wedding necklace from Singapore. Although intended for Malay matrimony, the necklace bears the Islamic symbol of a star and crescent, saving the gist of both cultures in one necklace.

, the auspicious Chinese Eight Immortals, to decorate the ornament unaware of its original symbolism. Another example of this cross-cultural interaction is a wedding necklace from Singapore. Although intended for Malay matrimony, the necklace bears the Islamic symbol of a star and crescent, saving the gist of both cultures in one necklace.

This beadwork tablecloth is the largest example of Peranakan beadwork, which is very characteristic of Peranakan artwork. An interesting aspect is that many of the motifs in the tablecloth, such as birds and flowers, are mostly European, with only a few Asian specimens. Nowadays, beadwork is valued as a cultural product and souvenir.

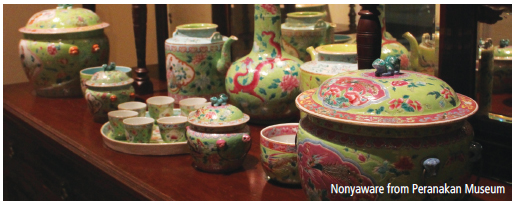

Nonyaware is one of the most recognizable items from the Peranakan Chinese community. It is made by Nonya (Peranakan women). Fortunate symbols are used with bright, vivid colors to decorate porcelain Nonyaware. What is notable is that Nonyaware shows Peranakan culture to be profound and sophisticated enough to establish its own style of ceramic art and craft.

Contemporary Art

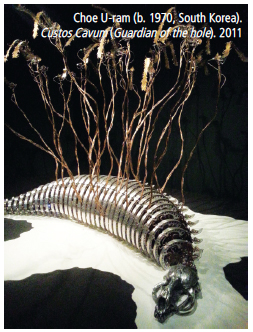

Singapore has the potential to be an art center encompassing not only Malay, but also Asian art in general. I had the chance to attend the Signature Art Prize of 2014 at Singapore Art Museum, an art competition featuring works by artists from the Asia-Pacific region. Some 105 were nominated from 24 countries, and 15 finalists’ works were on display - to my happiness, a Korean artist was one of them. He is Choe U-ram, and his piece is called Custos Cavum. He considers his piece alive which is why he says people do not come to “see” his art but to “meet” it. Meeting Choe’s sculpture in a foreign land was exciting. The territory for contemporary artists is broadening.

My friend who studies Korean Painting at Sungshin Women’s University once told me about the importance of creative space for artists; space provokes imagination and leads to novel inspirations. Such place is rare in Korea. In Singapore, I found one - LASALLE.

LASALLE is a nonprofit private institution of contemporary art, funded by the Singapore government. It was the archetype of imagination-provoking space; the design of the institute is by no means conventional. The walls of the buildings are made of glass so that anyone can see ateliers or lecture rooms, contributing further to the open space. Several ongoing exhibitions and shops are full of unique artwork and products. I even purchased a unique set of eco-bags at a student shop called WORKSHOP by McNally & Co, which was actually an art project in a form of an exhibition “designed to resemble a retail space.” This project aimed to explore consumer behavior toward art?the desire of consumers to own and thereby identify themselves with these unique items. I was dumbfounded at first but pleasantly gave in to how cleverly these LASALLE students had enlightened me to my own consumer fallacy.

I was envious of how Singapore has an environment of the artists, by the artists, and for the artists where creativity can blossom. In this century, when art is no longer just bourgeois luxury, but often a political tool and a mirror of society, really understanding the importance of art and artists in society is crucial, and Singapore is doing things right.

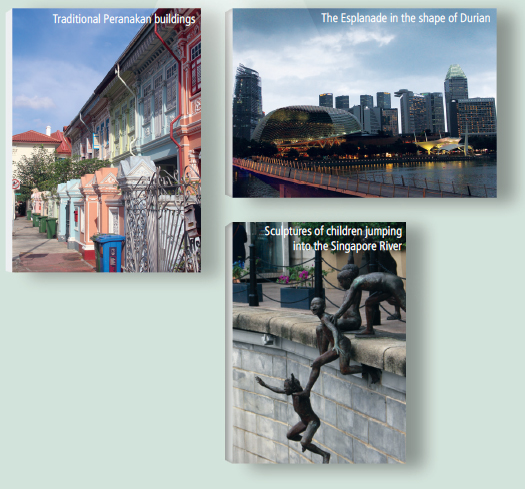

I would like to borrow Choe’s words and say, I met art on the streets of Singapore. Not only in front of fancy buildings as commissioned installations such as in Gangnam, but on walls, near the Singapore River, and in architecture in the form of graffiti, sculpture, and architecture. Graffiti does not look like doodles, but paintings on the wall. Sculptures are everywhere - not only near museums but even in unexpected places. Lastly, this city- state provides an amazing combination of old Hindu/Buddhist temples, churches, and mosques with new skyscrapers and buildings. As we say in Korea, better look once than to speak a hundred times. Above are the artworks I met in Singapore.

Throughout the trip, Singapore made me think about labeling. My belief is that art reflects the soul of people in the community and reflects society. If that indeed is true, Singaporeans must be accepting of different cultures, religions, and languages without any judgment or repellence, as we observe in the Peranakan necklace. They do not label or define others; what they are, they are. It has been common for us to judge everything in terms of dichotomy; good and evil, right and wrong, major and minor, major religion and pagan.

However, in Singapore, it is so natural that “different” people live distinctly yet together, and no one is wrong or wronged for being who he or she is. The multiculturalism in Singapore is not in the terms of western culture that we are used to; “melting pot” or “salad bowl” cannot describe the Singapore experience. Singaporeans of Southeast Asia are singular under an indefinable identity, and sometimes, indefinable is not a bad thing.

Singapore is becoming a leading hub of art in Southeast Asia; it was the first nation in the region to host special exhibitions of the works of Leonardo da Vinci, featuring scientific inventions as well as the alleged “earlier Mona Lisa.” Singapore,s Ministry of Education financially supports LASALLE to raise promising artists. Until now, western art has been the center of art industries, bearing western ideologies. It is about time that the world sees some Asian art. Why not spread the Singaporean sense of acceptance and the indefinable? It would be a great change for the better.

All photos credited to Kim Soo-yeon

Kim Soo-yeon

shunny03@uos.ac.kr