The difficulties that students face in housing can threaten their lives. Many students live with hazards, crime, and financial strain as they try to study while working to pay rent. The dangers are right next door.

In November 2014, a 22 year-old student at Korea University died after inhaling smoke from a fire at the goshiwon where she was staying. According to the Godaesinmun (Korea University Newspaper), the fire ignited from a mosquito coil that a student in the neighboring room had put under his bed. As the fire grew, smoke quickly filled the entire hallway. The shouts and screams woke her up, and when she opened the door, smoke instantly filled her room and smothered her. She died in hospital just over a month later. The male student, also 22, was later convicted of causing accidental fire and negligent homicide and sentenced to 16 months in prison.

Like many goshiwons, this one lacked functioning fire alarms, sprinkler systems, and escape routes, as fire inspectors confirmed in the Godaesinmun.

Students at the University of Seoul are also exposed to crimes and hazards. On June 26th, 2015, a male student attending UOS was arrested and charged with 10 home invasions and incidents of rape, including four attempted rapes, all perpetrated against female students living alone just outside the campus gate. The incidents started in 2013 and continued until May 2015. Police finally apprehended the perpetrator based on street video footage.

Violent crimes happen in the neighborhoods immediately surrounding the UOS campus more often than many people realize. In another example, on April 24th, 2015, a man assaulted a woman working at a stationery store with a baseball bat, in broad daylight, inflicting a head wound.

With these incidents in mind, students living near the campus worry about their security. Da-eun Shin (Dept. of Urban Sociology, ’14), a witness to the assault at the stationery store, said, “For a while, I was afraid to go out after the assault happened. The number of police patrols increased, and the streetlights, too, but the creepy atmosphere here still makes me tense.”

Yet, crime is not the only danger. Even the financial strains of working to pay rent can be life-threatening for students throughout Korea. According to The Kyunghyang Shinmun, a student at a national university in Kangwon-do drowned in August 2013 while working at a reservoir. The 19 year-old student was trying to carry a piece of machinery through a drainpipe. With the lack of oxygen in the drainpipe, he suffocated and fell face-down into shallow water.

This is a case with which many UOS students can relate. According to the article in The Kyunghyang Shinmun, the student in Kangwon-do had worked in various part-time jobs since graduating high school so that he could afford to pay his own rent and living expenses. One of his friends remembered him saying, “It’s physically demanding, but I do it because I have to.”

Although such incidents of violence and death are rare, they illustrate a deeper problem. Most students suffer because of their housing. In Korean society, particularly in Seoul, young people are already burdened by high rents and excessive deposits. College students are particularly disadvantaged because they are non-wage earning. If students want affordable housing, they often have to endure confining, unclean, or unsafe conditions.

In fact, housing has presented huge challenges for young people in Seoul since the 1960s. During the period of hyper-growth between the sixties and nineties, a great number of young people immigrated to Seoul to seek jobs. As the city’s population boomed, the real estate market could not supply enough housing, and the young had to accept some of the poorest conditions. Some buildings were crammed with rooms barely wide enough for an adult to lie down. These places were known as henhouses.

As time passed, wages increased, and apartments became common, with average housing conditions improving significantly. Like students in all parts of the world, those in Seoul still often live in very poor conditions, financially and environmentally. In Korea particularly, the gradual improvement in housing which society as a whole has seen, has had little effect on young, single people. Because of certain features in Korean politics, economics, and society, students have missed out on the progress.

Is Housing Affordable to You?

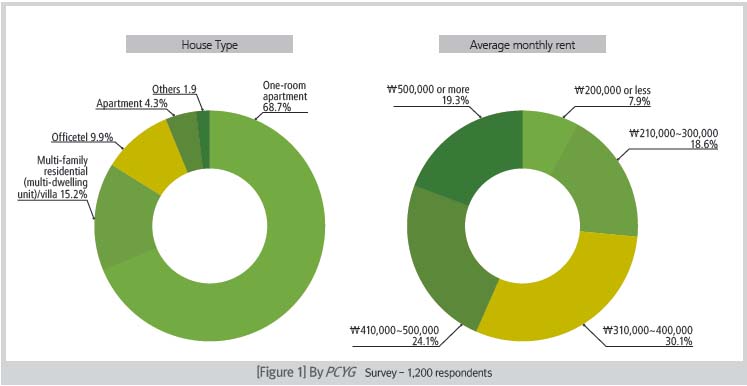

In January 2015, the Presidential Committee on the Young Generation (PCYG) published a report, Five-hundred Thirty Thousand Students in Need of Residence: A Survey of One-room Housing. In making the report, the government surveyed 1,200 students in the capital region on the quality of their housing.

For college students, the most common type of housing is the studio apartment, also known as a one-room in Korean. As seen in figure 1, nearly 69 percent of students were living in one-room apartments at the time of the survey. Multi-family residential, or multi-dwelling units (MDUs), are the second most common type, with 15.2 percent. The officetel, a type of building which contains both residential and commercial units, is the third most common for students, at 9.9 percent.

The most significant problem is that rent and deposits are far too expensive for young people, and especially for college students. The PCYG report

ed that average monthly rent was ₩420,000 (350 USD), with the average deposit being ₩14,180,000 (11,840 USD). More than 72 percent of students surveyed answered that they felt these expenses were burdensome. Market rent is also far more expensive than dormitory fees, which amount to ₩160,000 (133 USD) at UOS. In the same report, a male student at another university said that he would have no other place to live if he had to move out of the dormitory.

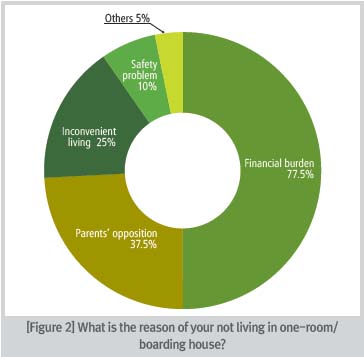

A survey conducted by The UOS Times corroborates the PCYG report (See figure 2). In the survey, 77.5 percent of commuting students said they do not rent near UOS because of the financial burden of doing so. Among students who rent, 76 percent said that average rent near UOS is excessive. A student from Daejeon commented that he found housing prices “four times more expensive” than in his hometown.

This cost is a burden even to those who have jobs. The Min-snail Union, a civic group working to resolve young people’s housing issues, conducted research in 2015 on the quality of housing for young people in Seoul. They reported that 63.7 percent of single households in Seoul are in the low-income group, earning less than ₩2,000,000 (1,670 USD) a month. Seven out of ten young single households spend more than 30 percent of their monthly income on housing, and no financial support exists for them. Many students, as well, have no financial support for housing, yet also cannot hold jobs.

Is Your Home Livable?

However, students not only face financial problems in their housing; housing environments present many difficulties, as well. In January 2015, the UnivTomorrow Research Laboratory, which conducts social research on people in their twenties, reported on the condition of university student housing in the capital region, including a survey of 1,068 students. Students living in boarding houses and goshiwon, which are privately-owned, off-campus dormitories, reported the lowest levels of satisfaction, with a score of 4.29 out of 7, with 4.71 being the average across all categories. Students living in campus dormitories and one-room apartments recorded 4.53 and 4.69, respectively. Students particularly reported discontent with soundproofing and privacy. Additionally, students in one-room dwellings expressed dissatisfaction over public safety, while those living in dormitories, goshiwon or boarding houses complained about inadequate living space. In goshiwon and boarding houses, ventilation and natural light were also severely inadequate.

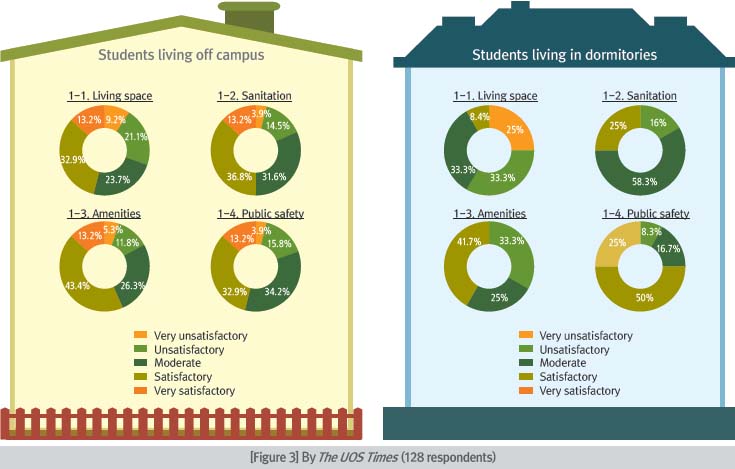

The UOS Times also conducted a survey of UOS students to gauge their satisfaction with dwelling conditions across four categories: living space, sanitation, amenities, and public safety. The UOS Times distributed the survey to students living in off-campus boarding houses and one-room apartments and in campus dormitories.

According to results, students living off campus are highly satisfied with amenities near their residences, with 56.6 percent describing the stores, restaurants, and other facilities as “very satisfactory” or “satisfactory.” However, their attitudes toward their residential spaces were quite different: 30.3 percent described their space as “very unsatisfactory” or “unsatisfactory.” Students expressed a similar level of dissatisfaction with sanitation and public safety—especially with public safety.

The UOS Times found that many student residences near the UOS campus had particularly poor sanitation and public safety. Jae-yeon Go, a real estate agent working outside the campus’s back gate, said, “Compared with those living near private universities, rather more UOS students find cheaper housing with inferior conditions. Some students look for semi-basement rooms and rooftop houses despite poor sanitation conditions.”

Then, there is the issue of crime. In a survey of 452 police officers on public safety in housing published in 2015 by the Korean National Police Agency, 70.3 percent of officers said that a one-room apartment or villa is most vulnerable to crime. This information shows how exposed students are to crime where they live.

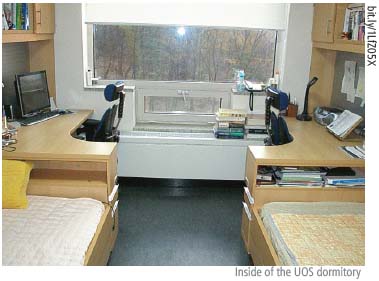

Due to the instability of the environment off campus, Korean students generally prefer to live in dormitories for safety and well-maintained conditions. At UOS, affordable dorm fees also appeal directly to students. In our survey, many students criticized the UOS administration for the low acceptance of residents into on-campus housing. Currently, the dormitories accommodate only 7.4 percent, far below the average of universities in the capital area, 17.4 percent. One respondent said, “Monthly rent at places near the campus has risen too much, and it is too demanding for students. I think that as a public university, UOS has a duty to ensure that students have places to live.”

UOS has responded to these calls for improvement. In October 2013, the administration announced a plan to expand its dormitories to accept up to 10.2 percent of students. This plan was in response not only to constant demands by students, but also to the evaluation criteria of the Korean University Accreditation Institute, which require that universities provide housing for 10 percent of students. However, UOS failed to receive a budget for housing from the Seoul city government, and construction has been delayed.

Among the four categories on the survey, students expressed the strongest discontent with the residential space in dormitories. The sum of “very satisfactory” and “satisfactory” was 8.4 percent, whereas the combined value of “very unsatisfactory” and “unsatisfactory” was 58.3 percent. On the other hand, up to 75 percent of dormitory residents said they found the security systems “very satisfactory” and “satisfactory.” In addition, the number of students feeling contented with amenities was higher than the number of those expressing content with sanitation.

A Legacy of Growth and Greed

We may attribute all of these problems ultimately to financial burdening, with origins in the period of rapid economic expansion. Indeed, the Korean economy owes a considerable portion of that growth to the real estate market.

Jeonse, a contracting tradition unique to Korea, has played a key role in the process. When a renter signs a Jeonse contract, he or she provides the leaseholder with a lump-sum deposit instead of monthly rent. This enables leaseholders to buy other property through mortgages or to earn high yields through other investments. The rapidly growing economy and inflowing population promised high yields.

One function of government is to prevent such distortion in the markets, but rather, it encouraged the practice of jeonse. As GDP increases through government and consumer spending, the government has continued to promote property deals in order to raise economic growth rates.

Hae-cheon Park, a professor at the Liberal Arts College of Dongyang University, called this economic relationship between lessor and lessee The Apartment Game, and titled his book the same (2013). In his book, Park said “the game,” to a certain degree, substitutes for a social welfare system as it distributes the capital accumulated through high economic growth.

As a result, property prices in Seoul increased to abnormal levels, which in turn developed an economic bubble. Because of high property prices, leaseholders had to put down more money in order to start a business, and they started to pass these expenses to renters.

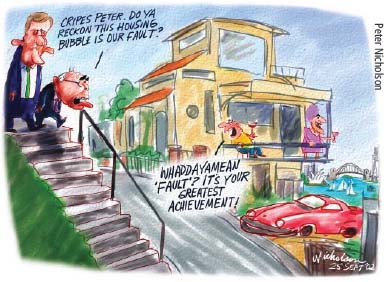

Even though the economic bubble is slowly deflating, many opponents of the current administration say that the government is still pushing for rejuvenation of the real estate market, rather than initiating an economic soft landing.

Interviewed by Newsis, Dae-in Sun, economist and representative for the research institution SDINomics, said that the current real estate market is like “a sinking boat.” Sun added, “The market will slowly continue sinking. We may all be wondering whether we should evacuate, but current government policy is telling to stay put. It’s like saying ‘hold on, we can make prices go higher.’ ” The Park administration’s economic policy well reflects this push. In July 2014, Kyung-hwan Choi, the Deputy Prime Minister for Economy, announced a new set of policies—which administration officials termed Choinomics— to promote property deals through the easing of mortgages.

However, according to Yonhap News, the ruling and opposition parties have both criticized the policy. Kwang-on Park, a congressman with the New Politics Alliance for Democracy, strongly attacked the policy, saying, “Choinomics is only a bomb-dumping-trick to shift debts onto the next government.”

Opponents further insist that as the government continues sustaining the economic bubble, property prices and rental prices continue flying too close to the sun and are likely to melt soon. In an interview with Yonhap Infomax, Masayuki Nakagawa, a professor of economics at Nihon University, warned that Korea could face the burst of the economic bubble as has Japan. Masayuki said Japan’s bubble economy was due to an immoderate easing of regulations and low interest rates, as we see in South Korea now.

Yet, there are many economists and policymakers who support the government’s drive for high property prices and lower mortgage rates. According to Aju Business Daily, Myung-suk Ahn, a property team leader for Woori Bank, said, “We can expect a soft landing in the real estate market with the government’s reflationary policy.” Aju Business Daily also reported that Hyun-ah Kim, a researcher at the Construction and Economy Research Institute of Korea, supports the Park administration’s policy. Kim said, “Easing of the loan-to-value ratio will encourage people take out mortgages from banks rather than from non-monetary institutions, thus qualitatively improving their liabilities.”

Nevertheless, even if current real estate policies benefit some in society, students do not feel the positive effects. High property prices have made universities reluctant to build or extend residential space for students, deeming it too expensive as an investment, thus leading to an extreme housing shortage. According to the Korean Council for University Education, universities in Seoul recruited a total of 77,905 students in 2015, while statistics published by Higher Education in Korea show that in the same year, university dormitories in Seoul could accommodate only 13.84 percent of students. The rest have to seek private housing, which often exceeds their ability to pay. Particularly at UOS, which has a limited municipal budget, financing is a more significant obstacle than at private universities.

Even if a university secures a budget, problems remain. In a university district, area landowners often object to extending dormitories, claiming that extensions lead students to turn their backs on outside housing and eventually harm their business. According to the Korean newspaper News1, when Kyunghee University held a public hearing on dormitory extension in 2014, some locals vehemently criticized the university’s plan, even yelling during the hearing.

These conflicts also arise from a lack of social consultation. In an interview with The UOS Times, Dong-hun Oh, a professor of urban administration at UOS, said “Korean society is still not accustomed to the institution of the dormitory.” Oh added, “Many Western societies already have a consensus that college students do not yet have financial independence, thus seeing the necessity of investing social resources in dormitories.”

Professor Oh also pointed out that college students are not participating in political action, leaving politicians uninterested in their issues. Oh said, “College students should learn how to exercise political leverage in order to make politicians work for them.”

Of course, there are some policies in place to support student housing issues. In 2011, the Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH) started supporting Jeonse housing for college students. Under one program, Jeonse Rental for Colleges, LH selects students with financial needs and helps them look for housing. It then lends Jeonse deposits up to 75,000,000 KRW(62,630 USD). However, the housing standards that the program requires often leave students with a low number of residences to choose from, with many participants never finding places to live. When the program started in 2011, LH planned to support 1,000 students, but only 107 were successful.

The national government has been constructing Haengbokjutaek, or happiness houses, as one solution. However, Kyung-ji Yim, chairperson of the Min-snail Union, pointed out that rents and deposits are still too expensive for many of those in need. She explained that this is because LH and the Seoul Housing Corporation, two organizations in charge of the program, want their investments repaid as quickly as possible in order to reduce their own liabilities.

Looking for a Way Out

Professor Oh expressed pessimism about resolving the situation, saying no good short-term solution is available. However, he favorably assessed the policies that the Seoul city government have taken to improve housing. The government has operated a social investment fund since 2012 to settle social issues and develop the market for social investment, supporting organizations such as workers’ cooperatives and corporations developing solar energy. Above all, there is the policy of social housing, the construction and rental business plan for working classes and vulnerable social groups. While the government provides public housing, social housing normally involves non-profit organizations or housing associations connected to public resources. Those bodies utilize public funds to provide affordable housing. The Min-snail Union also establishes housing cooperatives which connect member investment to public resources. According to information from the Korea Social Investment organization in 2015, the Seoul city government has spent about 70 percent of its social investment funds since 2013 in social projects including social housing. Oh said, “Social economy, a market system which pursues the value of community interest, rather than only profit, has not taken hold in Korea. Thus public institutions should still provide most of the costs and infrastructure.”

Oh also emphasized the role of public institutions like UOS, which is now setting up a project with the Jungnang-Gu office and Myeonmok High School to provide college students with wage-earning opportunities and dormitory rooms in exchange for tutoring high school students. Although it only selects few students for now, this kind of policy will become an important asset to public schools like UOS.

In the housing environment, police are implementing anti-crime measures to reinforce neighborhood security. They have increased the frequency of patrols and number of streetlights. UOS students have suggested still other solutions. Ji-yoon Jung (Dept. of Urban Administration, ’15) said, “I hope there are more systems like citizen group patrols to prevent crimes in limited zones, and expansion of the city’s late-night chaperone services for women.” She added that she is grateful for convenience stores that provide employees with instant emergency hotlines to the police. In these systems, employees who feel threatened can pick up the store telephone receiver for 3 seconds, and receive an instant connection to police dispatch. Da-eun Shin, the student who witnessed the assault on the stationery store clerk, proposed beautification of residential streets by changing the color of street lighting. She said, “I expect this would result in a more calming environment, reducing the crime rate.”

The many problems with residential space have no short-term resolutions; they are deeply related to the mismatch between supply and demand. There are not enough rooms in decent condition with lower rents, and there is poor access to housing information. The Min-snail Union provides a website at http://minsnailunion.tistory.com with specific information on a variety of housing—public rental houses, public dormitories, boarding houses, also specific information. More websites like this can further alleviate the housing shortage.

Meanwhile, the UOS administration has confirmed its decision to expand campus dormitories, but has still failed to receive the necessary budget. An official in the university’s Facilities Division said, “Designs for the expansion were completed in 2015, but we have not secured the budget because the city government has put low priority on the project.” However, the student housing problem is no longer temporary. It has become the starting point for a vicious circle of poverty, threatening their academic lives. Jihwan Hwang, the director of the University Dormitory stated, “Society should consider the dormitory to be an educational facility, not a welfare facility, so that it will invest significantly in student housing.”

Professor Oh points out that there will be no easy way to resolve the student housing problem: “Every policy should go through a process of reaching social consensus among all members of society, and this can take a very long time.”

There are active movements in the cooperative associations such as the Min-snail Union, but these are not sufficient to assert student rights. Without personal attention and participation in the housing issue by speaking out in the community and on campus, solutions will be delayed, and students will not be able to defend their basic rights - living in normal homes.

Hye-joon Suh

hjsuh789@uos.ac.kr

Shin-ho Ahn

ash906@uos.ac.kr