It is not a new kind of problem at all that students activism at South Korea’s universities is slowing down. Actually, it has been an intractable issue ever since July of 1987, when the heat of pro-democratic protest had reached its zenith and finally defeated the military dictatorship; by filling all the streets of Seoul and even holding sit-ins at a cathedral, citizens were able to make the dictator into submission and draw the constitutional amendment that regulated the direct election of presidency. After achieving their primary goal, democratization, student activists gradually lost their momentum as they did not have such an agenda to unite the whole students as when they were fighting against the dictatorship. As university student bodies lost their influence on social issues, they also gradually lost popularity among students.

Nowadays, students are paying so little attention to student activities that it is no wonder that many universities are lacking students to run their student councils. Given that student bodies of many universities functioned as a pivotal figure at the scene of pro-democratic movements, deterioration in student governments can lead to crisis of student activism itself. Unfortunately, it already became an epidemic among universities; including UOS.

Besides UOS, many universities suffer from decline of student activism. Yonsei University, which is often regarded as one of the most prominent in terms of student activism, failed to elect its student council president for the first time in 55 years for there was no candidate. Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS) has never had a successful election since 2011. In 2016, HUFS even failed to have a re-election for student president so they had to form a special committee. Korea University Newspaper, already pointed out this in 2011. In their article, “As a community, does student society exist?,” Park Jong-chan, former vice president of student council at Korea University, said that he “never have seen a crisis like this, watching student society in the school for 10 years.”

It also has become a common sight at UOS in recent years that an election fails just because no student files for candidacy. Siwon, the Student Council in 2016 which started from re-election for no candidacy, even ended its term in the exactly same situation just a year later.

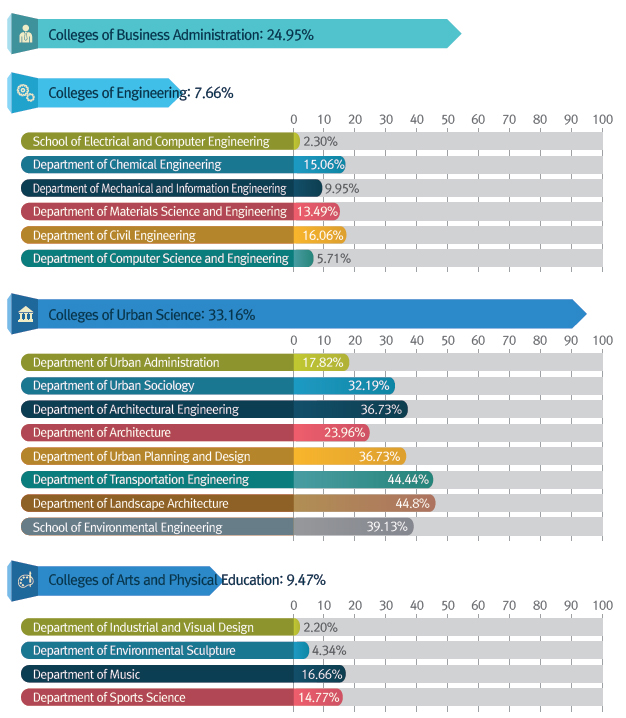

In addition to lack of candidates, low vote turnout is also a problem. Not only the general student council but also students of each department often have had a hard time electing their head to meet minimum vote rate required to validate the election. As shown in Figure 1, average vote rates by colleges, despite deviation, are all less that 40 percent. When it comes to vote rates by departments, except for the Department of Korean History which scored 54.26 percent, none of these departments made 50 percent for their election and for some departments the rate was less than 10 percent.

“Slowdown of student activities on and outside of campus is not a unique problem to UOS. It is rather a general trend among universities,” said Shin Ho-in, former president of the UOS Student Council. He agreed with that student activism has lost its way after the democratization, saying, “They had the specific goal then, but afterwards the meaning of student activism became uncertain,” he added.

Slowdown of student activism means not only lack of concern from general students but also the changes in activities done by student bodies. Certainly, student bodies in the 1980s tended to focus on political issues, especially democratization of the nation. By contrast, the focus has moved more to schools, curriculum, and educational funding in recent years. Some might read this change as apathy towards social issues. However, are students really indifferent to the changes in society? In fact, there are still quite a few students who actively engage in political, social and economic activities.

In late 2016, about 800 UOS students made a public protest against the national government as it had been revealed that President Park Geun-hye had long been manipulated by a mere civilian during her presidency. The students marched down from the campus to Cheongnyangni Station and held a rally in the square. Even after their own march and rally, they joined the larger crowd of citizens in Gwanghwamun Square to denounce the government. Also students made signature campaign to express their political opinion denouncing President Park Geun-hye.

This assertive, willing participation of students denies the point of view that current students are so indifferent to social issues. Actually, it just seems like students are on the streets instead of campus.

Student activism in the history of South Korea can trace back to the early 20th century, when Korean Peninsula was under Japanese colonial rule. After Japan annexed Joseon in 1910, Korean students continually played an important role in protest for independence of their nation. For instance, Lee Kwang-soo, a famous Korean author, and other students who studied in Japan issued a manifesto which defined the annexation as injustice and called for the liberation of Joseon. These efforts enormously influenced on the independence movement in Korean Peninsula, triggering the famous Sam-il movement in 1919.

Unfortunately, as President Park Chung-hee put the martial law all over the nation, anti-government protesters faced ruthless crackdown and were forced to go underground. Some prosecutors in national security department even fabricated cases for their own benefit. Innocent victims of those fabricated cases could barely be reinstated after tens of years passed.

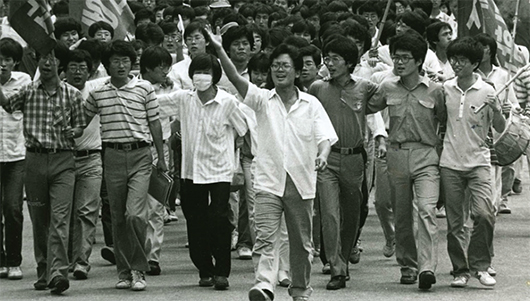

However, even the violent repression of the military regime could not keep the enthusiasm from growing. Entering the nineteen eighties, activism among collegians came to maturity in terms of its philosophy and organization. After experiencing the Gwangju Uprising in 1980, in which not only students but also different civilians stood up against Chun Doo-hwan’s military government, student activism turned its direction more to populism from liberalism. Rallies and protests got bigger, propaganda was elaborated and university students formed independent student bodies. Increased publishing of books about ideology stimulated recognition and discussion about the society. In the end, student activism as a part of civil protest reached its peak in June Struggle in 1987 and overthrew Chun’s military regime.

Nowadays, “student activism in Korea is facing decay” became a common topic. As mentioned above, great amount of universities suffer from lacking candidates of election and poor voter turnout. About the reasons that cause this change, several explanations have been suggested.

One of the most often claimed reasons is that student activism has lost direction after the collapse of dictatorship. According to The Herald Business, Student Council as a central figure of activists has actually ended after June Democracy Movement, as they seemed to complete their mission. Students started not to want university student bodies to be their representative, as it became almost impossible for such organizations to reflect all the members’ opinion when there were many so different agendas. In addition, bureaucratic and elitist features of some student bodies even made other non-government students to dislike their presence.

There also is increasing competition among universities and among students themselves, according to Choong-Ang University Graduate School Newspaper. Steering for neoliberalism in 1990s, South Korean government started to lift a restriction on university entrance quota and to foster competition among universities. Stricter curriculums promoted rivalry among students, rather than encouraging them to focus or band together on various issues.

Tough economic conditions are making the situations even worse. OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) announced that youth unemployment rate in South Korea recorded 10.7 percent, which is 0.2 percentage point higher than that of the previous year and is the worst since 2000. Former UOS Student President Shin Ho-in also pointed this as an obstacle that keeps students away from activism. “Driven into excessive competition for a job, it tends to be no good for college students to voluntarily participate in student government activities,” Shin said.

Looking students themselves, a great number of college students no longer feel that they can play any role to make change in the society. According to Kim Yun-tae, professor at Korea University said, “As college enrollment rate in Korea went beyond 85 percent, self-awareness among college students as an elitist figure leading social changes is becoming faint.” This kind of helplessness is not an exception even to the ones who run a student body. Shin Ho-in had a comment to make on this problem. “It is sometimes a dilemma. The thing is that it does not matter anyway when they are just doing fine but it immediately becomes an issue when there is a mishap or a mistake. It is for not only the general student council but also every single unit of student government activities.” So this risk makes student governors stick to their minimum responsibility rather than encouraging and recommending students to get involved in activities, Shin pointed. “Actually, students’ interest and credit are the fuel for many students who are voluntarily participating in various positions.”

Prevailing individualism is also doing its part. Among many reasons why individualism spread, one major cause is 1997 Asian financial crisis. Professor Chun Sang-chin at Sogang University said, “In 1980s, Korea’s economic condition was really favorable so students could easily pick up a job.” For students had less concerns for livelihood, student activism could be more prosperous. “However, as the crisis struck, the situation changed a lot and it suffers now.”

These causes range over various sides and some of those are what the generation ahead had never experienced. Certain causes such as excessive competition between students are getting worse as time passing by and the decline of student activism is expected to die hard.

All those evidence seem to be saying that university students today are not as interested in student activism as they were in the past. Poor turnout of voter for university elections support this thought. However, you must doubt it when you check it out and see that how many students are actually engaging in movements to change society, politics and economy in various ways, some aspects of which are different from those of the past.

Whenever it is discussed that students participation in social movements are diminishing, student activism is often defined as the “traditional” fashion that derived from protests in 1980s and this diminution of the fashion is interpreted as downfall of student activism itself. However, the recent trend shown in the protests in the late 2016 says that it is not university students’ participation itself that is diminishing.

While many students were rallying outside against the Park Geun-hye government, students at different universities, even ones in the provinces, gathered in Gwanghwamun Square in order to censure the government. Of course there were student bodies rallied under their own banners waving but they did not form large files as they often did in the past. Many students just came alone or with a few colleagues rather than joining those groups. “I wasn’t convinced by others but it was just my feeling, anger at the way the things are being done now,” said Kwon Young-min, a student at UOS. Being interviewed by SBS News, Lee Taek-gwang, professor of global communication at Kyunghee University, suggested the prevalence of individualism as the cause of this change, as well as weakening of student bodies. “being used to the custom that regard an individual as the fundamental and absolute unit, people can feel uncomfortable with protests that are led by certain organizations for their own sake,” Lee said. The news then presented instances of Korea University as an back-up example about this notion, in which students denounced their student council for trying to issue a manifesto that does not coincide with students.

This is what we see today; trends in student activism are changing, if not changed already. While big collective engagement in social activities is decreasing, individual or small-group participation is filling it up. Student bodies as a sort of boot camp that help students adapt to social engagement is no longer a valid model.

The key factor that enabled this change is advance in technology that facilitated rapid exchange of information. Students can just teach themselves by crawling the web instead of joining a big group of other students. They can simply check all the information needed and go out alone or with small groups of colleagues as they want. For an instance, a website claiming President Park’s resignation is on operation since late 2016 and continuously providing various information such as protest schedule and related news reports. Also, promotion is more quickly and widely spread on the web than in the real world. Just a few clicks can make suggestions for engagement reach the whole country, almost without any cost.

The ease in the exchange and promotion necessarily led to diversification of student activism. While student activists in eighties focused their capabilities almost solely upon taking to the streets for democratization, today’s different groups are focusing on various issues including social welfare, environment, economy, gender equality, minorities and animal rights.

Yet, diversification and fragmentation do not mean that students cannot stand as a large group when a collective, strong protest is needed. When the anti-government protests in the late 2016 scored the unprecedented participants of over two millions, students at different universities gathered as one to voice together. Also, in order not to forget the sinking of MV Sewol and to call for more safe society, university students gathered and formed solidarity as a subordinate organization of the large 4.16 solidarity which has similar goals.

Being driven into the tough situation, university students are often considered to be focusing only on their own business, being reluctant to engage in politics or other issues; they are said to be individualists. Accordingly, established press take notice of decline in student bodies and reports that students’ indifference on social circumstance is undeniable truth.

However, the evidence suggest that it might not be true that university students are indifferent to politics. Outside of campus, university students are actually assertively expressing their political opinion and participate in social movement more than ever, as they did in late 2016 through early 2017 when they simply could not bear it anymore. It is the ways they stand up and speak, which are quite unlike those of students in the past. Perspectives of those who show concern for student activism are might have to turn their eyes to the streets, rather than campus, to witness the change the new generation has brought.

Ahn Shin-ho

ash906@uos.ac.kr

Jung Jae-in

zanej0418@uos.ac.kr