On February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military staged a coup, detained Aung San Suu Kyi and other key government officials, and declared a year-long martial law. Because the NLD (National League for Democracy) party achieved an overwhelming victory in the 2020 election, recording an 83 percent approval rating, the military alleged voter fraud and requested that the election commission recount the votes. However, when the government rejected the claim, the military mounted a coup and seized political power. The Myanmarese have been under a democratic government for the past five years and thus refuse to accept the junta that took power in the coup. Protests to overthrow the junta took place immediately beginning on February 2, 2021. The citizens informed the international community of Myanmar’s situation and appealed for support. The unarmed civil population went to the streets to demand that power be handed back to the citizens in front of armed police. In contrast, the military suppressed the peaceful protesters by firing live ammunition and rubber bullets, and as a result, hundreds of citizens were killed.

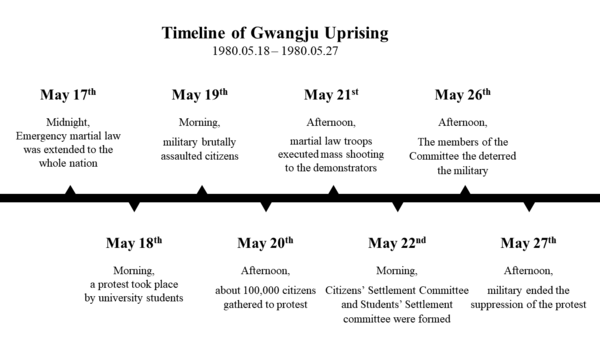

Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement of 2021 is quite similar to the democratization movement in Gwangju, South Korea, on May 18, 1980. In 1979, Chun Doo-hwan, a South Korean Army major general, staged a coup and took control of the military. He wanted to seize political power, so he proclaimed nationwide martial law on May 17, 1980. A student protest against the situation then took place in Gwangju on May 18. When the university students demonstrated in the city in response to the closure of the school, the government sent troops to suppress the protest. The citizens who gathered to determine the situation confronted the military and police. As the protest escalated, the army began mass shooting at the citizens. The uprising was suppressed by armed airborne troops early on May 27.

-The similar aspects of the two countries’ struggles

The background and progress of the two countries’ pro-democracy movements are similar. In both countries, special forces were mobilized to repress the protests, and they used violence against demonstrators who demanded a democratic government. Both armies used weapons on unarmed civilians and caused numerous casualties. Both Myanmar and Gwangju, South Korea, concealed information on the protests such as by announcing that the government was not responsible for the deaths of the citizens and by reporting a lesser death toll. Moreover, following the coup, Myanmar’s military also blacked out the Internet and social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Junta arrested journalists and increased the sentence applied to journalists’ charges from two years to three. At the Gwangju incident, the press prepared articles to announce the tragedy in Gwangju, but the incident was not reported due to the government’s control over the media. While the media of Gwangju were struggling, the government distorted the Gwangju Uprising as a “riot” and reported it as such across the country.

Despite the violence of the nation’s power, efforts have been made on the part of the civil society of the two countries to provide support for their democratic movements.

-The integration of citizens

Despite this adversity, Myanmar's struggle has also served the function of uniting its people. Myanmar has difficulty integrating the national majority, the Burmese, and its ethnic minorities. More than 20 ethnic armed groups have been fighting against the state for their rights and autonomy. However, following the coup, minority rebel groups in Myanmar have had confrontations with Myanmar’s military in support of the democratic government. In Myanmar, all levels of society are participating in the disobedience movement in various cities.

The same situation occurred in Gwangju. More than 200 university students began protesting in Gwangju, but two days later, the protest turned into a massive uprising involving more than 100,000 citizens. Citizens created their own newspapers on behalf of the media, but they did not function properly. The demonstrators reflected all levels of society, including high school students, university students, office workers, housewives, merchants, and social activists. Taxi drivers carrying the injured also staged car protests. As the crackdown intensified, citizens voluntarily formed a civilian militia to fight back. On May 22, the Citizens’ Settlement Committee, consisting of about 20 priests, pastors, lawyers, and professors, was formed to handle the situation.

-The role of the media

In spite of continued media repression, Myanmar’s citizens are actively asking the international community for solidarity through the Internet. The citizens are appealing for support in their demonstrations through a hashtag movement, and videos of the protest are spreading within social media. Countless images and articles regarding the situation in Myanmar have been distributed on the Dark Web.

On the other hand, in regard to Gwangju in 1980, the nation was not actively informed of the local situation due to press censorship.. Instead, foreign journalists came to Gwangju to cover the situation at that time. Journalists from Japan and the U.S. collected news in Gwangju and wrote articles. In particular, the protest in Gwangju was broadcasted throughout West Germany on May 22 through the efforts of German journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter, known for the movie “A Taxi Driver.” Additionally, members of the U.S. Peace Corps helped foreign journalists with interpretation to facilitate the conversation with citizens.

-Continuing international solidarity

It is a positive sign that the international community is also responding to Myanmar’s situation by issuing a statement condemning the human rights abuses committed by the Myanmar military and imposing economic sanctions. The South Korean government announced a statement condemning Myanmar’s military violence. The South Korean politicians, regardless of the ruling and opposition parties, passed a resolution at a plenary session on March 26 to denounce the military coup, restore democracy, and release detainees. On March 12, the South Korean government also addressed the topic of South Korean tear gas and tear gas projectiles, which may have been used to suppress protests in Myanmar, stating that they will strictly examine strategic materials such as chemicals as well.

While the government was supporting the pro-democracy movement in Myanmar, the international community has also mobilized, empowering the citizens of Myanmar. A hashtag movement is spreading around social media to express support of the Myanmar protesters, and various organizations are also supporting the uprising in Myanmar, expressing concern over it. The support activities of university students in Myanmar were led by the student council. The solidarity in the local community is dynamic. Civic organizations are holding a memorial service for Myanmar’s innocent dead citizens. In Gwangju, which suffered a similar tragedy, more than 100 social organizations formed a group called the “Gwangju Solidarity in Myanmar” to continuously demand citizens’ attention.

The Gwangju Uprising ended in failure after being suppressed by the military. Nevertheless, it had a significant impact on South Korea’s democratization, becoming the cornerstone of the June Democratic Struggle in 1987. In contrast, the pro-democracy movement in Myanmar is ongoing. Numerous Myanmar citizens continue to die due to the military’s violence, and the protesters’ desire for democracy seems far away. It is time for Korean university students to pay attention and support the uprising of Myanmar citizens, remembering our pain from our own democratic movement as well as its significance in Korea.

How, then, can Korean students help Myanmar citizens? First, students can provide financial support to Myanmar’s citizens to continue their civil disobedience campaign. Many citizens suspended their occupational work and took part in the demonstrations. Therefore, citizens need money to cover their cost of living, receive treatment, help other arrested citizens, and pay tribute to those who are killed by the military. University students can provide practical help by donating money to institutions or organizations that raise funds to help Myanmar's protest.

Second, students can express their support online. Myanmar’s military is suppressing the media and controlling the Internet to disconnect Myanmar from the outside world. Publicizing what is happening in Myanmar via social media and voicing support through hashtag movements can help its citizens continue their protests.

Finally, it would be helpful to send letters of participation to domestic companies and governments. As consumers, students can demand that South Korean companies that invest directly or indirectly in Myanmar's military should not give them money. Furthermore, students can ask the government and the National Assembly to pressure Myanmar's military more strongly. This pressure would be a significant movement to show that the international community will not tolerate the situation in Myanmar.