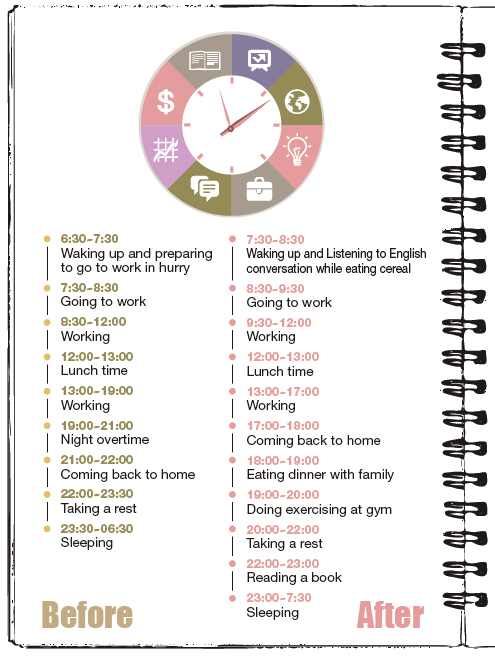

Current social trends are moving everyone toward the values of work-life balance and small but definite happiness. These values are also influencing labor policies in Korea, making their way into work-life revisions of the Labor Standards Act, decreasing maximum working hours from 68 to 52 per week. This new policy addresses the fact that Korean employees worked an average of 2,052 hours per year in 2016, ranking second among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. According to numerous studies to find correlations between working hours and human health, working long hours leads to low labor productivity, high suicide rates, and the lowest happiness index. Despite of these results, the Korean government did not provide workers the right to rest.

Apart from the idea of work-life balance, there is another concept that Koreans are adopting: small but definite happiness. The way I started and finished my shorter day is an example of this second concept. The changes may have been small, but the benefits were definite. Having time to listen to English conversation while eating cereal is one such small, but significant instance of happiness. Having dinner with my family was another. Although each person has a different standard of happiness, many are more likely to seek small but definite instances of happiness; after all, it is impossible to sustain constant happiness in this hard society. work-life small but definite happiness.

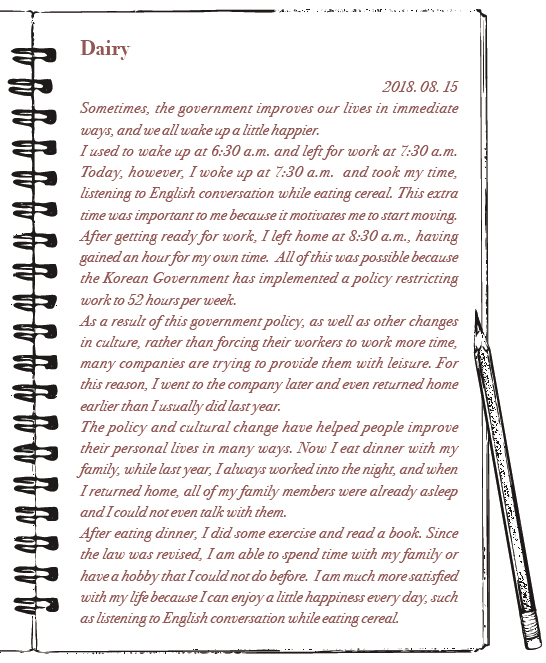

Changes in society’s view of happiness

Korean society has long tended to promote ideas and routines that will increase overall happiness. In the 2000s, for example, the concept of Well-Being encouraged people to pursue harmonies between physical and mental health. In the early 2010s, Healing became a trendy concept, encouraging people to take care of their tired bodies and minds by taking breaks in their daily routines. In 2017, the idea of YOLO - ‘You only live once. - became a fad, encouraging young people to spend their money enjoying their present life. These days, the trend is to emphasize work-life balance and small but definite happiness lead our society trend.

The meaning and origin of work-life balance

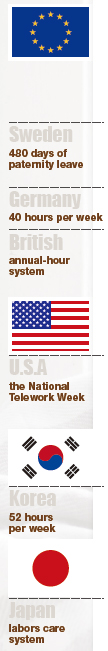

Work-life balance describes balances between time allocated for work and other aspects of life. The term work-life balance originated in 1986 in the U.K. and U.S. In 1980s and 1990s, companies in the U.K. and U.S. began to offer work-life programs. Originally, the first wave of these programs primarily supported women with children. However, as time went on, work-life balance became a global concept. These days, work-life programs are less gender-specific and recognize other commitments as well as those of the family. As employees in global communities also want to be flexible and control their own work and personal lives, the Korean government is keeping pace with the global trend with its new 52-hour work week. Thus, Korean companies and workers are now striving to carry a work-life balance out.

Why is work-life balance on the rise in Korea, particularly, and at this time? Perhaps it is a response to the rapid changes that have driven this country in the last 50 years. People who lived before 1988 concentrated on living itself, while people born after 1988 have lived in economic affluence. Because of these changes in lifestyle, they now place greater emphasis on their self-satisfaction rather than money. This change also affects company culture.

The meaning and origin of small but definite happiness

The concept of small but definite happiness is similar to work-life balance, but whereas work-life balance applies specifically to employment, this term applies to everyone, in general. It is the idea small dreams can be achieved more easily in daily life than achieving big dreams, such as buying a house, marriage, or achievements in career. The term was small but definite happiness first used in an essay by writer Haruki Murakami in 1994. In this essay, this novelist defined this concept as “happiness [that] is trivial and simple in daily life, such as cutting fresh bread by hand, seeing your arranged underwear in a drawer, and the feeling of a cat coming into the blanket and making sounds during a winter night.” In other words, this kind of happiness is a small pleasure occurring in the middle of a hurried daily life. In other languages, the concept is similar to small but definite happiness Au Calme in France, Lagom in Sweden, Hygge in Denmark, and Kindredness in English.

Why are Koreans suddenly enthusiastic about the idea of small but definite happiness now? Nowadays, Korean young people tend to give up on personal goals or values such as buying a house, marriage, building friendships, and having a baby because of the pressures of Korean society. For this reason, young Koreans are pursuing small but definite happiness to escape from their stressful lives. In other words, the concepts of work-life balance and small but definite happiness have existed before, But now, these ideas are emerging as responses to hard lives with difficulties such a buying a house, wedding expenses and raising children.

Cases of work-life Balance

To understand how these two concepts are at work in society, let’s take a look at a few examples from around the world.

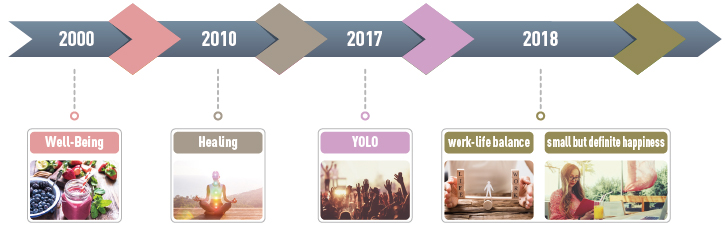

Europe

In Europe, there have already been many attempts to reduce working hours since the 1900s. Currently, Germany, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, and France are the European countries with the lowest annual working hours among OECD countries. There are many approaches to reducing work hours, often called flexible working throughout Europe; such as Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. These countries have implemented a four-day work-week system. As a result, the average number of working hours per week in those countries is 28-33.

In Sweden, the most important feature of the flexible working system is that both married men and married women can take 480 days of paternity leave when they give birth or adopt children. France adopted a work week of 35 hours in the 1990s. Employees who work more than 35 hours a week can then take vacations equaling the amount of overtime.

The Germany has the lowest annual working hours ? 1,363 in 2016. They have adopted a policy of 40 hours per week, and if German workers work more than 40 hours a week, they can have a vacation equaling their overtime.

The British flexible working system includes an annual-hour system that divides contract periods into two quarters, in which employees can work during one quarter and take personal leave during the other quarter, according to their needs.

Thus, in Europe, work-life balance is a commonly observed value providing various flexible working systems for most countries.

United States

In the U.S., average annual working hours are 1,783, just above the OECD average. As the number of double-income families increased sharply since the 1980s, the U.S. government and workers began attempting to improve their working conditions by devising a flexible working system. One campaign for a flexible working system is the National Telework Week, which promotes telecommuting and encourages workers to work from home once a week. This system results in the “win-win” outcomes that flexible work options have, for both companies and their employees.

Korea

Korea has not valued work-life balance for long compared to other developed countries. This is because Koreans did not have the economic affluence that permits flexible employment until after 1988. Changes are seeking to balance work and life, but efforts are not sufficient yet. Only companies and public institutions with more than 300 workers are required to implement Labor Act revisions, so far. This is not enough to fully meet objectives.

Japan

Japan has the most similar working conditions to Korea. They have eagerly tried to implement a flexible working system to cope with a reduction in working population resulting from both?a low birth rate and an aging society. What is unique in Japan is that the government assists workers in managing stress. There are four types of care, including self-care, which helps workers manage stress by themselves, line care by managers, industrial health step care implemented bosses, and resource care conducted professional institutions.

Cases of small but definite happiness

As we mentioned before, the concept of small but definite Happiness is conveyed in different ways in many languages. As it was coined by Haruki Murakami, the term small but definite Happiness is used in Korea and Japan. Au Calme used in France, conveying a sense of quiet. Au Calme refers to a relaxed state of mind and body without stress. This is the attitude one has while enjoying a leisurely coffee at home. Lagom is used in Sweden to mean suitable. Someone seeking lagom prefers spaces filled with comfort and simplicity, leading to a balanced life without greed. Hygge is used in Denmark to signify cozy. One who is experiencing hygge feels happiness through a simple life being created in a cozy, relaxed atmosphere - wearing a warm sweater and drinking a cup of coffee by a fire. In the U.S., the term Kinfolk, which originated from Kinfolk magazine in Portland, originally referred to one’s family or relatives. However, kinfolk now also refers to a simple, slow lifestyle through which people closely associate with nature, including relatives, friends and the neighborhood. The origins and meanings of these words are different, but all refer to pursuing a comfortable and simple life set apart from a busy life.

All of these terms also connote a reduction of clutter and a simplification of surroundings, thereby also reducing stimuli and emphasizing calm. They all emphasize minimalism. Those who seek a simple but definite happiness will also want to reduce clutter and simplify their physical surroundings.

In Korea, the concept of a simple but definite happiness is actually not new; it may be most similar to the ancient Buddhist concept of hwadu, which connotes an awareness of fundamental truth in the activities of everyday life. Like the Scandinavian concepts, hwadu may be expressed in design and architecture, with surroundings that emphasize stone and wood from nature, and few embellishments or furnishings. All of this simplification will lead to more meditation, in any given moment. The issue for today, then, is how to emphasize hwadu in our modern, fast-paced, over-stimulated society.

The positive effects of policies for work-life balance

In Germany, when it is exactly 8 p.m., the streets become quiet. People are at home with their families, and most of the markets are closed. This is also true every Sunday, all day. Thus, Germans have to go to the grocery store in advance to buy their food for Sunday.

The German example illustrates what happens when policies restricting working hours of workers are observed strictly. The concept of valuing work-life balance is taken for granted by German employees and employers. Germany is one of the representative countries that guarantee the right of workers to be happy with their work and life.

In contrast, streets in the cities of Korea are bright with the lights of buildings and neon signs all night, an environment that Koreans take for granted. In this environment, many people are still working through the night. However, some changes have recently occurred in Korea. Koreans have started paying more attention to their own happiness, concentrating less on earning money. Already, we are beginning to see how these changes affect our society positively.

Increasing interests in self-improvement

According to Sinsaegae Department Store, participation in the store’s Culture Center, which offers courses to the general public as well as its employees, have increased this fall semester, and they have enlarged their classes to meet the demand. In particular, the number of participants in their twenties and thirties has more than doubled. Such programs are also underway at Hyundai Department Store and E-mart. Their growth of programs is possible because more corporations are complying with the laws restricting working time to 52 hours a week. Workers who once could not spend time on their hobbies can now turn to having new hobbies.

Another sign of this change is that sales of hobby-related goods, cultural goods, and healthcare have increased recently. According to G-market, sales on gloves for martial arts have increased more than 1,000 percent in the first half of this year alone, and clothes and videos for yoga have also increased by 125 percent. Moreover, tickets sales for musicals or classical guitar performances have increased 125 percent. These numbers show that workers are paying more attention to their self-improvement and cultural experiences in their free time.

Workers can improve the quality of their lives by concentrating on self-improvement as a result of valuing work-life balance. These self-improvements not only help individuals, but also strengthen the competitiveness of society, and may hold strong economic benefits. Korean culture will develop if the arts receive more continuous public attention.

The changing culture of get-togethers after work

Many people not only feel the stress of hours at work, but they also continue their relations with co-workers at the requisite get-together after work. They say that it is like an extension of work and that they cannot refuse to attend, truly adding stress for them. However, the culture of the get-together has changed recently. According to a businessman who is working at a major company, the atmosphere that forces workers to participate in get-togethers is disappearing. Instead of getting together after work, they tend to have lunch together, often enjoying high-priced food, usually paid for by the company.

This trend is also affected by the new law restricting working hours. In a survey by Saram-in, an employment agency for Korean corporations, 55 percent of respondents say that refusing to attend after-work get-togethers is possible.” In addition, 55 percent of respondents also say that the frequency of get-togethers is decreasing. However, more than 30 percent responded that there are disadvantages if they do not participate in get-togethers. Thus, although corporate culture is improving, more change is still needed.

The positive effects of small but definite happiness

Byeon Jae-jin (School of Economics, ’15) said that he has become much happier since he began pursuing his own small but definite happiness. He feels grateful for even small things in his life. His efforts at small but definite happiness include making and drinking a juice in the morning in all seasons. While Byeon may, or may not, be happy by attending outings with others, or by saving up to eventually buy a house, he knows he can be happy today when he makes a juice by and for himself.

He answered that he has pursued small but definite happiness since he started preparing for K-SAT when he was a high school student. Like other students, Byeon also felt stressed because by his studies. However, since he decided to seek his own happiness, he has found relief from his difficulties.

Byeon also believes strongly in the power of small but definite Happiness. As we can see in his case, the strongest advantage of small but definite happiness seems to be that it gives us the power to endure such difficulties.

Negative effects of rapid transition to the society valuing work-life balance

As we stated, there are many changes in the society in the positive ways for work-life balance and small but definite happiness. However, because the transitions of society are becoming more rapid, some problems occur in this process.

Are people being forced into work-life balance?

Many people complain about the new law of restricting working time. As we mentioned above, this law restricts the working hours by force. If companies do not follow the law, they will be penalized.

Additionally, some workers also complain because they think the law infringes on their rights to work freely. Many want to work more than 52 hours a week because they need additional income. Work is a crucial part of their lives, so if income is too low, they may have to find second jobs, possibly leading to more stress and fatigue than they felt before the law was implemented.

Thus, rather than leading to greater competitiveness and economic benefits, this restriction may lead society to lose energy and income. Is the government right to effectively lead workers who want to work more into resting more? Whether to pursue a work-life balance or not should be one’s choice, not prescribed by others.

No consensus on work-life balance

Bae Geun-hang (Dept. of International Relations, ’09) has worked in a large company for three years as a businessman. He says he has seen the effects of the new restrictions. “Some changes have already happened in our daily activities,” he said, pointing to the way workers now have to clock in and out at offices. “But these small changes are not the most important effect of the law.”

The small changes that Bae describes are in place so that people obey the law, not because of efforts to improve quality of life. It seems that a consensus has not yet been reached between employers and employees, so at this point, the policy seems superficial. According to Bae, neither employees nor employers are interested in work-life balance. They follow the rules so that the owners of their companies can avoid arrest or penalty.

Are young people limiting themselves to trivial happiness

Some people argue that if young people only pursue momentary happiness, ubiquitous anywhere, they may end up confining themselves to a small box of experience. They assert that young people should aim for higher goals so that they can develop themselves.

The Satori Generation in Japan is an example of this phenomenon. The term refers to young people who were born in the late 1980s to 1990s and are not interested in earning money or achieving success in their lives at all. Satori means achieving enlightenment, so this generation lives without any greed for luxury, cars, or large houses. This attitude is one social consequence of the long recession in Japan, in which young people had to give up all unnecessary spending.

The Satori Generation and the trend of small but definite happiness are similar in some ways. Both occurred in order to overcome economic and social depression, during which many young people became rather lethargic. If society’s lethargy becomes worse, Korea may also encounter a Satori Generation. If so, society may lose much of its vitality.

However, Byeon, who enjoys his own small but definite happiness said that he disagreed with this opinion. Although he could see that some of his friends are satisfied only with transitory happiness, small but definite happiness is just the driving force for him to achieve highly prioritized objectives. According to him, if you have obvious objectives in your life, small but definite happiness can perform a role in relieving one’s stress in the course of achieving higher goals.

Besides, we may have to wait some time before the changes find their way into the larger Korean society. Far from Byeon, when we met Bae at Teheran-no, he showed us the beautiful nighttime skyline of that area, where offices still do not turn off the lights. He said that these lights are proof that work-life balance is still not making its way into society, as workers are in their offices well into the night. Despite the increasing attention to work-life balance, it seems that we still have a lot of details to solve before society can relieve all of its excessive competitiveness.

Kim Kyung-sun

kyungsun16@uos.ac.kr

Park Jun-young

pjy970108@uos.ac.kr